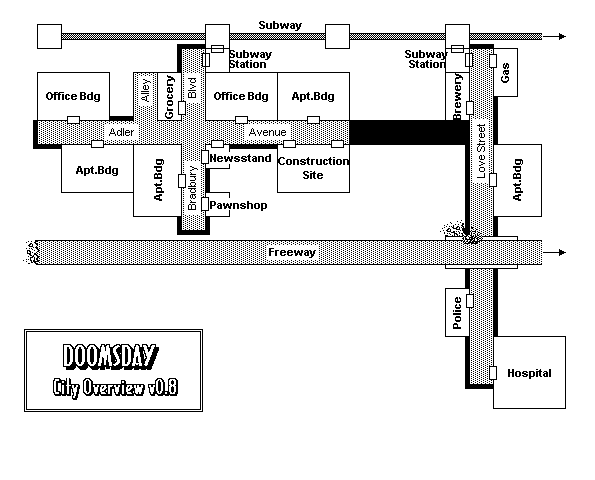

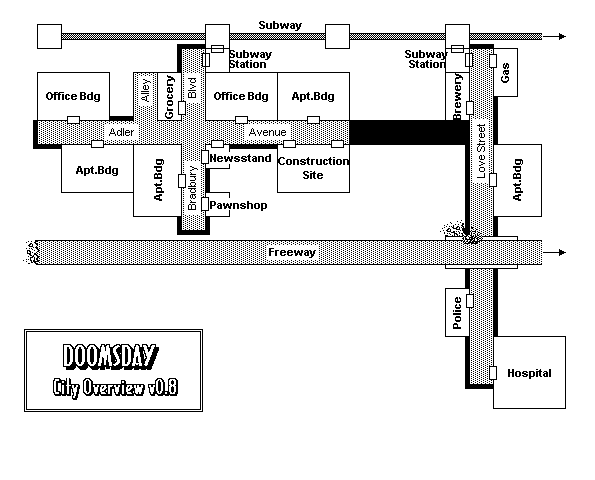

Doomsday Sample Script

A sample location from the unpublished “Doomsday” CD-ROM game, in a custom script format designed by Tod Foley. Written for Amazing Media, April 1995.

doomsday_sample_script

A sample location from the unpublished “Doomsday” CD-ROM game, in a custom script format designed by Tod Foley. Written for Amazing Media, April 1995.

doomsday_sample_script

Mediatrix is a LARP presented for the Interactive Fiction SIG of the International Interactive Communications Society in 1994; an allegorical head-trip to a satirical scenario of our internetworked multimedia future. Participants role-play the mighty officers of international industries, wielding globe-spanning power in a warped world of politics, programming, and propaganda (oh yeah — did we mention paranoia?)

HANDBOOK

14 January 4437: En route to the city of Sanctuary, Blandisford Barter encounters an Elven minstrel on the Bridge at Three Roads Crossing. The RunePlayer introduces himself as Rimsel, and informs Barter that he has been sent by the Council of Deneldor to oversee the halfling’s progress. Unfortunately, some evil priest’s spell bound him to this bridge several days ago, and he is unable to overcome the magick. Blandisford uses the Codex of Truth to call upon the power of the deity and free his Elven ally, who repays him with a much-needed clue…

11 January 4437: Bearing west from Sanctuary, Rakasha is stopped by a party of Deneldoran WayGuards, sent by the Council to secure the Bridge at Three Roads Crossing. Their leader, Rimsel the RunePlayer, is disgusted by the Evil One’s presence in the land, and the group engages Rakasha in a duel. Quickly dispatching the lesser foes, Rakasha turns upon Rimsel, whose eerie fluting begins to weave a potent spell in the air. "You shall not cross this Bridge!", Rimsel sings through his flute. Rakasha shouts a quick obeisance to his evil deity, resisting the spell so mightily as to reflect it back upon the Elf, who is rooted helplessly to the spot. Rakasha leaves Rimsel behind as a symbol of his superiority, and continues west…

Note: the second encounter occurred prior to the first.

MultiMedia programmer Robert Edgar has pointed out that one of the key defining factors of Interactive Fiction is *Relativism*. In order to create and maintain a realistic "world", the writer must be able to shift gears, to interpret events, objects and characters from different points of view, perhaps simultaneously.

The "GameMaster" or "RealTime Processor" of the presentation must utilize a holistic writing style which may be termed "ambistructural" – meaning that it relies upon both constructionist and deconstructionist techniques. The two entries above, taken from the Campaign Calendar of Thear (my own long-running fantasy world), serve as a good example of ambistructural processing.

Note that the second encounter took place before the first one in GameTime (such things happen when running a large-scale campaign). When Blandisford first met Rimsel it was just a random encounter roll which I decided to spice up a little bit. I added the stuff about the Council and the spell which stuck him to the bridge in order to give the Blandisford character a test/reward; if Blandisford saved the minstrel, then I’d give him the clue he needed to proceed to the next adventure. But then, when Rakasha came along (three days earlier in GameTime) and I rolled a Guard encounter at Three Roads Crossing, I couldn’t resist tempting fate a little, and decided on the spot to put Rimsel there. It took very little maneuvering on my part to make Rakasha’s Player hate the pompous little guy, and I may even speculate that the depth of this reaction had something to do with the dramatic way in which the dice cooperated with the story, causing Rakasha to roll a critical success on his resist roll (this oft-noted phenomena is the only reason why dice are better than random number generators; many Players feel that they have some degree of psychic control over their dice, and who’s to argue?)

In any event, I had to quickly deconstruct the first encounter in order to construct the second one, thereby tying my world together in a seamless, logical whole. Only when they got together later did the two Players realize what had occurred, and by then, it seemed as if I had planned the entire thing all along.

Because of the complexity of game worlds, it seems like an obvious idea to use computers to run Interactive Fiction presentations. After all, no human can immediately consider the hundreds of tiny variables which may be taken as bearing upon a situation, and respond with a visual and auditory presentation of the results of those calculations. However, the state of the art of IF programs is still severely limited by the lack of original ideas and our current inability to write programs which can "think" in an ambistructural way.

A good GameMaster runs from a mixture of prepared notes, random dice rolls, and sudden flashes of inspiration. If done well, Players will have no idea whether an event was preplanned, dice-dictated, or completely ad-libbed. The illusion will be complete.

The original blurb stated:

“The only book in the market that focuses on tips and techniques that allow the reader to more effectively use the resources of the Internet.

— Explains search techniques and the use of kill files to filter information

— Features interviews with various Internet leaders

— Offers tips, strategies, and techniques for optimizing the use of the Internet”

This was sorta true in 1994, when I co-wrote this book for SAMS Publishing. Today, the book’s diverse assortment of tricks for the net’s earliest public applications is of mostly historical interest. Of particular note are some of the interviews, conducted by me, of 90s-era internet luminaries including Mitchell Porter, Patrick Kroupa (aka Lord Digital), Nathaniel Borenstein, James Parry, Paco Xander Nathan, Fred Barrie and Steven Foster, and the WELL’s Gail Ann Williams.

Foreward by James “Kibo” Parry.

An article about “Cyberion City,” a text-based interactive environment at MIT. Originally published by bOING-bOING magazine, April 1993.

musers-not-losers

A Report on the Production of Ghosts In The Machine

The circle is still chanting softly as the CyberGoddess faces Darwin down. She turns to address the participants: “All those who find the defendant Darwin Krayne innocent as plead, say Aye” (participants respond); “And all who find the defendant guilty of crimes against humanity say Aye” (participants respond).

(The strength of the two responses will be compared to determine Darwin’s sentence.)

– from Ghosts in the Machine

Interactive Fiction (“IF”) is the currently popular term for any form of nonlinear scripted entertainment, from Role-Playing Games and MUDS to multimedia CD-ROM environmental simulations. A fledgling devotion somewhere between art and science, IF Design relies upon a sort of relativistic thinking which is a fairly recent addition to the artist’s toolkit — an ability to expand one’s view of what was once perceived as only a narrow dimension of functionality, and to envision processes in terms of fields and possible relationships, rather than lines and discrete data.

The mental shift necessary to utilize these skills is not unlike that required by a “traditional” programmer who decides to tackle the strange new world of Object-Orientation.

As a GameMaster and IF Designer, I get to hear a lot of questions which reflect the boundaries of this paradigm shift: “How do you write a system which can resolve any type of attempted maneuver, even if it never occurred to you?”; “How do you create a world which is open enough to appear unlimited, but closed enough to allow you some degree of control?” and “If it’s a game, how do you win?” (Of these questions, only the third possesses an easy answer, also in the form of a question: “Well, how do you win in life?”)

As If Productions (AIP) answered these questions directly and by example at the third annual CyberArts International conference with two presentations of our experimental IF theater piece, Ghosts in the Machine. A live, interactive, gothic-cyberpunk horror-mystery, “Ghosts” takes place at a grand party held in the year 2042, in celebration of the opening of the world’s first true DNI (Direct Neural Interface) network. Although the central story revolves around Information Mogul Darwin Krayne and his family (both living and dead), the game mechanics were designed to support scores of individual PlotLines, each of which was dependent upon the actions, decisions and intelligence of the Players (the audience members). Presentation involved the real-time coordination of twenty Co-Actors, a dozen specialized Game Operators and a “multi” of media: prerecorded audio and video segments, a live DJ, live video mixing and interactive QuickTime movies, with a continually-revolving crowd of anywhere between ten and fifty Digi-MIDI-Cyber-Technophiles.

Participants underwent a short and informal “personality inventory” prior to entering the game. Pre-generated Player Characters (“PCs”) were arranged in three-dimensional arrays of four cells, and two databases were used (that’s 128 Characters, for those who didn’t want to do the math). The interview was based upon the well-known Myers-Briggs Personality Inventory, a modern derivation of standard Jungian Typology. Bravely, our intrepid Interviewers fielded the traffic-jam of Cybernauts outside, relaying their data to PC Assignment Managers Jordan Foley and Catherine Seitz via Radio Shack radio headsets. ($35 each, and they worked pretty damn well!) Jordan and Cat acted as a creative team, engineering “Player-to-Character Transition” from both sides of the theater wall.The interview procedure helped to indicate which type of Character Players desired, and allowed us to predict Player behavior to a (very) limited degree, but most importantly, it afforded us a short “grace period” in which to pass the corresponding information to our Stage Manager and “central control unit” Torey Holmquist, who then primed the Co-Actors and triggered plot events on-the-fly.

Ghosts in the Machine Example Player Character Form PROFESSION: Socialite/Gadfly

(from PCA Managers' Database)

APPROACH: Observer

ELEMENT: FIRE

PERS.CODE: ESFP

SOCIAL CLASS: Upper/Corporate

GOAL GROUP: Nosey

TELESPACE ACCESS LEVEL: 1

TELESPACE PROGRAMS: "Call Map," "Move To...," "Go Back," "List Contents," Search For...," "Copy...," "Cut Line"

BANK ACCT #: 72197

BALANCE: $1,500,000

CASH ON HAND: __________

MOTIVATOR: You want gossip. You want to know everything about everyone at the Krayne's party, or anyone *related* to anyone at the party. You are not above spending $$$ to learn the juicy details.

RUMOR: "Klio Veritt" is actually a society reporter, here undercover as an investor for a acquisitions conglomerate.

Based upon answers given in the interview, each Player received two important pieces of information known as PlotSeeds: one “Motivator” and one “Rumor.” While the Motivators — prewritten descriptions of “typical” Character Class goals — were coded into the PC database, Rumors were selected (or even written) on-the-fly by the PCA Managers, ensuring that each Player had a pertinent link to a currently active PlotLine.

The presentation included one “Primary” PlotLine, which could be resolved in only one of two ways. “Secondary” PlotLines were developed around supporting Co-Actor Characters and hourly themes, and each possessed a number of possible resolutions (many possessed no specified resolution at all). “Tertiary” PlotLines were comprised of clues and props given to Players, which drove them to seek out other Players or props, or to enact sequences which did not radically undermine the higher tiers. There were, of course, a number of red herrings thrown in for good measure. No indication was made to Players that these distinctions existed.

One of the key operating principles of the system involved encouraging the Players to take an active hand in their own PlotLines. This was done by showing good faith wherever possible in dealings with Player Characters (except when the Co-Actor Character doing the dealing had an already-established bad reputation). We tried always to reward Players whose actions and lines of questioning indicated that they were actively involved, either by selling them what they wanted, giving them a clue, or directing them to a character who might help them. Remember: The GameMaster is in the business of losing – a good GM may push you up against the wall, but the best stories are the ones where you beat him in the end.

Nothing helps real-ize your reality like placing a different reality next door to it. For Ghosts in the Machine, multimedia/graphic artist Craig Halperin created over fifty large-screen displays of a TeleCommunications Matrix we called TeleSpace. We simulated verbal Player-control of the ten-by-ten foot graphic display using a Hypercard system (written by Craig), which controlled the projection of QuickTime movies through a RasterOps 364 ColorCard to a Barco Data PC projector.In effect, we had designed two games — running simultaneously side by side — which used the same pieces: the characters and the clues. The “Party Game” involved the creative use of social engineering skills and finances, while The “TeleSpace Game” gave people a chance to play hacker and utilize their analytical skills a bit. Participants “traveled” through TeleSpace by issuing commands to a Co-Actor playing an artificially-intelligent electronic Guide. These commands were relayed via headset mic to a hidden Operator who controlled the visuals on the big screen. The result was a larger-than-life representation of realtime movement through a vast multidimensional cybernetic environment. Players could hack their way through ICE, obtain illegal access to electronic funds and information, and bring this stuff back into play in the “Party Game” room. As was evidenced by the constant bottleneck outside the TeleSpace room, this was undoubtedly one of the most popular parts of the presentation.

Well, we learned Friday that neither system was up to handling the load required of it. The nearly constant flow of Players and PlotSeeds kept our PCA Managers up to their necks in work, and the TeleSpace system was plagued by a bug which forced it to crash once or twice an hour. Craig and I stayed up for the second night in a row as I redesigned Motivators and automated the PCA process, and Craig debugged TeleSpace. By 11:00 Saturday morning we were ready to run, and the testimonies of returning Players rewarded our labor. The system had evolved considerably within a twenty-four hour period, and participants seem to agree that the new design was far more user-friendly. The TeleSpace simulation only crashed once, and that had a little something to do with the fact that we had been running 80 amps through 40-amp circuits…

Ghosts in the Machine may or may not ever be presented again as such, but for us at AIP it was an important experiment; a query into the desires of multimedia audiences, an attempt to simulate a fully immersive, interactive display by using live actors, and a decisive step toward a better understanding of the art and science of IF. Ultimately, our goal is to inhabit our own HyperTheater, which will make full use of computer-assisted stage and audio/visual technologies (such as MIDI Show Control), in order to automate as many parts of our productions as possible. This will allow the human Co-Actors, Managers and Operators to concentrate on the “fuzzier” aspects of this new paradigm — like logic, detail, and elegance — at least until the machines can do that for us, too. As If Productions is interested in hearing the opinions of any CyberArts-goers who participated in the “Ghosts” presentations, so that we may better understand people’s expectations and desires for future live interactive productions. We will attempt to respond to all mail personally. If you have any input, please feel free to contact us.

-12 Feb 1993